Subterranean Urbanism

In this research project we have been investigating the phenomenon of underground housing in Beijing’s basements and bomb shelters. While incredible in concept, when one considers the history of western rapid urbanization, immigrants in cities like New York also lived in overcrowded basements. And with the current incredible densities in megacities around the world, urban planners are starting to seriously consider the subterranean city.

The first published paper can be downloaded here: “The Extreme Primacy of Location: Beijing’s Underground Rental Housing Market,” Cities, 52(2016): 148-158.

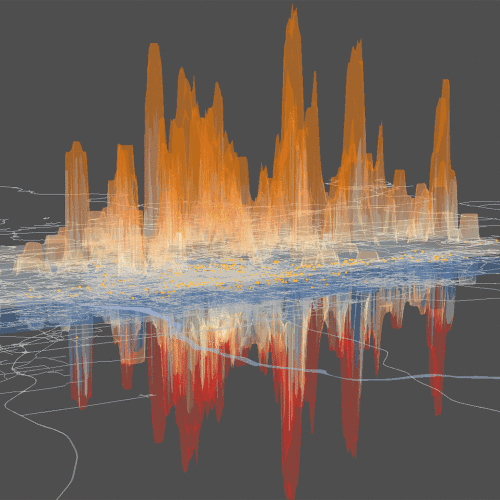

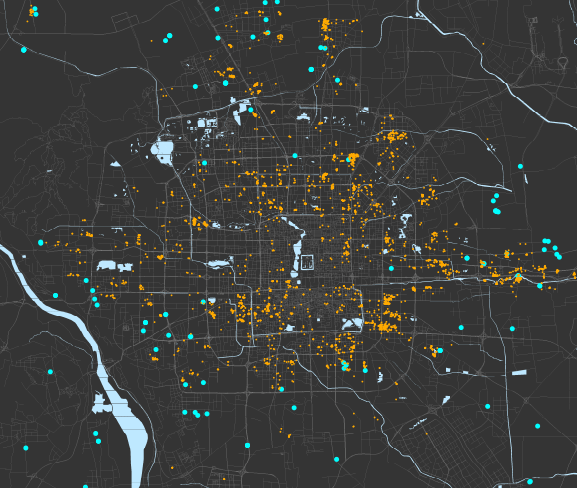

The orange dots show the location of the 3,385 underground rental units we found advertised for rent online during 2012-2013. Meanwhile, the blue dots show that affordable housing projects are located on the periphery. Also, only people who have hukou, the household registration permit, are eligible to apply. The roughly 10 million migrants without hukou need to find housing that they can afford.

We have been developing two lines of inquiry in this project. One statistically analyzes Beijing’s little studied subterranean housing market in the context of the city’s larger housing market and public affordable housing programs. The emergence of this sub-market indicates a demand for housing that neither the formal housing market nor public housing programs yet supply. This market study shows the relative priorities and preferences in price levels, location, and housing amenities of the middle-lower income population, particularly migrants without hukou.

Our findings suggest that this housing market is relatively affordable at roughly 20% of typical renter’s income but higher priced alternatives to migrant housing in the urban village housing on the city’s periphery. The market also indicates a demonstrated strong preference to be located so near employment as to be able to commute by foot and bicycle. These strong preference will be a challenge for future affordable housing solutions in Beijing’s high-priced land market.

The second line of inquiry asks more qualitative questions. The first concerns identifying the array of living conditions in underground units. Are they all terrible and could some actually be considered livable? Second, we seek to understand how the underground unit function as a part of renter’s livelihood strategies? What kinds of jobs and incomes do residents have and what are their commuting patterns and work hours? Third, what are the kinds of governance arrangements that organize the above ground and underground residents? What factors can we identify that might account for more or less successful governance situations of underground residents with immediate above-ground residents.

During 2013-2014, research teams of 18 Peking university students visited underground sites around the city and eventually developed case studies of 24 underground living complexes located in 17 residential communities in Beijing that included interviews of residents below ground and above ground, field surveying, and photography.

One of our striking findings was that people above ground and below ground have often mentioned concerns about “security,” and how little contact the above ground and below ground residents typically have. These factors have created an other-ing of migrants, who are dubbed the “rat” population. However, above ground constitute they constitute 40% of the population and are part of the everyday labor force.

This project has been covered by the following media outlets:

This project was made possible by funding from the MIT MISTI China program. USC also allowed me a year’s sabbatical at Peking University and the Peking University-Lincoln Institute of Land Policy hosted me as a visiting fellow. I am also indebted to Peking University Professor Lu Bin for collaborating with me on this project. And there were many wonderful students research assistants who helped on this project. At MIT: Yafei Han, Qianqian Zhang, Cressica Brazier, and Yuqi Wang. At Peking University: Fan Xing, Jiang Xin, Shuake Wuzhati, Tian Lu, and Zou Linyi. Additional Peking University student research assistance was provided by: Wen Tianzuo, Ding Yuchen, Li Jingwu, Wei Taoran, Xue Hongmu, Chen Shuai, He Zeya, He Xianhua, Li Feiran, LI Xiao, Zhang Lina, Zhou Guoqiang, Huang Bowei, and Guo Han